The Scots language and Scottish Gaelic are both experiencing a bit of a revival right now. Maybe not on a large or systematic scale, but if Twitter is anything to go by more and more Scots are showing an interest in these two languages. Between Len Pennie’s Scots Word of the Day, Alistair Heather’s documentary Rebel Tongue, and Duolingo’s very popular Scottish Gaelic course, it does feel like there’s a growing interest in both languages.

But alongside this revival, there is also a backlash. A notable example has been Unionist blogger Effie Deans claiming to have lost her way to Fort William due to bilingual road signs (despite there only being two roads into Fort William). Then a journalist named Tony Allen-Mills snarkily claimed that someone’s name was fake because it is Gaelic. It’s also not rare to see Union Jack Twitter regularly in the replies of both Scots and Scottish Gaelic content creators claiming that both languages are made up by Scottish nationalists in a desperate attempt to reject Britishness.

It’s not just Unionists though. Even independence supporters like to claim there is some clear-cut divide where all Unionists speak the Queen’s English and it’s only independence supporters who care about saving Scots and Gaelic. It’s not unusual to witness comments such as “the Unionists are at it again” when negative comments arise about either language. These comments aren’t only found on the hell-site that is Twitter either; I’ve spotted my fair share of them in the Gaelic Duolingo Facebook group.

I’m not here to talk about saving either language; that’s a wider conversation about structural linguistic justice. Instead, I’m going to lay down why neither Scots nor Scottish Gaelic is a nationalist language and why the myth needs to stop. I also concentrate more on the Scots language because I grew up around it and identify as a Scot. I am learning Scottish Gaelic and care about its survival but I am not a Gael.

I spoke Doric growing up, but didn’t always support Yes

I grew up in Aberdeenshire and was raised within a Scots speaking family, specifically Doric which is native to the North-East of Scotland. The maternal side of my family speaks Doric or, at the very least, with a broad Aberdonian accent. My dad speaks with an Aberdonian accent but tends to use English vocabulary (as a side note: my paternal grandfather is from Ayrshire).

Whenever people claim that Scots only exists in poetry, it obviously clashes with my personal experience. My mum affectionately calls me her wee quine and she asks for a bosie rather than a hug.

My mum, however, can switch to Standard English when she needs to. Just like many people who live in the UK without English as their first language, she doesn’t flounce into work as a nurse and start confusing patients with a language they might not understand. You probably do know people who speak Scots as their first language (Scottish Gaelic as well) but just don’t know it because they default to English in certain situations.

I’m going to state now that my native tongue is English. I can understand Doric because I grew up in a household with a Doric speaker, but when I try to speak the leid it’s a bit broken. When I speak to my mum at home, she’s speaking Doric while I’m responding in Standard English. Between the school system, being exposed to more English speaking media than my parents were, speech therapy and moving away from Aberdeen over 10 years ago I have a generic Scottish accent.

My family have mixed views on Scottish independence. I do support independence but used to be a Unionist and only changed my mind a month before the 2014 referendum. My parents support independence and have always been fairly warm to the idea. Some of my wider family are No voters though — but that doesn’t change the fact that my mum’s side of the family all understand Doric.

I support Scottish independence on the grounds that the Union is not working for Scotland and I believe that we could achieve much better things without Westminster. I am not Yes for the sake of Yes. In my heart, I was a devo max girl, but since that is clearly not happening I’ve chosen independence between the two binary choices I’ve been offered. Growing up in a Doric household didn’t influence my feelings on Scotland’s constitutional question. Even as a Unionist I had a lot of time for Doric as it was a leid I was raised with. I was also always supportive of Gaelic and have never once cried at the sight of a bilingual roadsign.

Learning Gaelic was practical for me, not emotional

When I decided to start learning Scottish Gaelic last year it wasn’t because I’m a raging nationalist; it was because I spotted people using it on Twitter and the penny finally dropped that I should be at least conversational in what is an official language of the country I live in. It had nothing to do with my decision to support independence, a decision I had made five years earlier. If those two things were connected, then it was a very delayed reaction.

Gaelic has come in handy for me, despite being regularly told that I should learn a more useful language. Useful? Like French? I can speak tourist French but never have the opportunity to use it unless I’m in a French-speaking country (which doesn't happen that often). People in Scotland speak Gaelic as their mother tongue and one year later I’ve used my Gaelic more than I’ve ever used my French. If you think Scottish Gaelic is a dead language you’ve not been paying attention.

I also have a Gaelic name and my recent decision to use the stràc (that acute accent) was no more than wanting to spell my name the Gaelic way. I’m not trying to advertise my political leanings through my name, though I have been asked if that’s why I use it.

Several Unionist MSPs support Gaelic and Scots

It’s not just me who's feelings towards Scots aren’t influenced by their political leanings. Peter Chapman, Conservative MSP for North East Scotland, is a Doric speaker and works hard to promote the language. Here’s a video of him addressing the Scottish Parliament in Doric and talking about the problems the leid faces. Just last Christmas, he released a charity CD of him reading Doric poetry.

With the Holyrood election coming up, there’s a #ScotsPledge being run by Oor Vyce that candidates can sign up to and promise that they’ll support the Scots leid in Holyrood. It already has cross-party support.

As for Scottish Gaelic, at the tail end of 2020 Conservative MSP and Orangeman Murdo Fraser took to Twitter to defend the language against Effie Deans, who was yet again having an anti-Gaelic outburst. I wonder how she feels about a prominent Tory MSP pointing out that you don’t need to be an independence supporter to want to protect a language with a long history in Scotland?

For balance, let’s look at pro-Independence MSPs who support Gaelic and Scots. Most notably is Kate Forbes, SNP MSP for Skye, Lochaber and Badenoch, who is fluent in the language. It was Kate who caused controversy by suggesting Scotland build Gaelic only housing estates where people have to speak Gaelic to live there (which I am supportive of).

Despite many Union Jack Twitter accounts insisting that the Yes supporting parties want to ban English, there are Yes politicians who have never publicly stood up for Scottish Gaelic or Scots. Nicola Sturgeon herself hasn’t said anything about saving Scots or Gaelic (I even went for a quick Google there, just to check, and didn’t find anything). I also personally know Independence supporters who never spell my name with the stràc, never mind trying to save the language on a larger scale.

Speaking Scots or Gaelic is largely dependant on where you grew up

I think at this point I’ve made it clear that support for Scots and Gaelic doesn’t neatly tie up with someone’s opinion on Scotland’s constitutional future.

What does tend to have an influence on someone speaking Gaelic or Scots is where they grew up and what language was spoken around them. Peter Chapman was raised in Aberdeenshire, Murdo Fraser is from Inverness, and Kate Forbes is from the Highlands. All of these pro-Gaelic and pro-Scots MSPs were raised in areas where these languages have a higher percentage of speakers.

Here’s a wee graphic from the 2011 Census in Scotland showing where each language is most widely spoken, Scottish Gaelic on the left and Scots on the right:

As you can see from the images, Scots and Scottish Gaelic are more heavily spoken in certain areas of Scotland, making it a regional divide than a political one. I grew up in the North-East of Scotland, which is the large dark blue triangle along the east coast. When you look at the map it’s not much of a surprise that Scots is a language that I can understand, given that I grew up in the Northeast.

The same goes for Scottish Gaelic. I first heard Gaelic spoken by natives in a shop in Harris in 2009, confirming to me that it is not a dead language. Harris is one of the islands covered by dark green off the north-west coast. You can see a full break down of the Census data for Gaelic here.

If you were to compare these maps to the map announcing the results of the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014, you’ll also see that there is little alignment between areas that speak these languages and areas that voted Yes.

The councils that voted Yes were Glasgow, Dundee, North Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire (coloured in green). None of these councils lies within the areas of Scotland where Scots and Gaelic are widely spoken. Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, where there are more Gaelic speakers than anywhere else in Scotland, voted no by 53.42% which isn’t out of line with the rest of the country.

As for Scots, Orkney and Shetland voted No in high numbers (67.20% and 63.71% respectively) which are coloured dark blue on the map. Aberdeen voted No by 58.61% and Aberdeenshire voted No by 60.36% — which are both also dark blue on the map. The Northern Isles and Aberdeenshire also get a lot of stick from Yes supporters for still having sizeable support for the Liberal Democrats and the Tories. Dundee was the only area of Scotland where there is some overlap between a high percentage of Yes supporters and a high-ish number of Scots speakers.

In some ways, you have to forgive some Scottish people for thinking both languages are only used for ceremonial reasons. If you live in the Central Belt of Scotland you are a lot less likely to have accidentally stumbled upon Scots and Gaelic in your everyday life. You may also have a lot less motivation to learn either language.

Both languages have been around longer than the Yes movement

It’s also worth noting that Scottish Independence is a relatively modern movement. I am 30 years old and I can remember when Scottish independence was something that a small percentage of the population supported. The SNP was also only formed in 1934, making it younger than my late grandmother who, yes, could speak Doric.

In contrast, Scottish Gaelic is believed to have arrived in Scotland between the 4th-5th Century from Ireland. While Scottish Gaelic has changed a lot over the centuries, calling it a nationalist language when it pre-dates the Act of the Union of 1707 and the independence movement is a bit far-fetched. Meanwhile, Early Scots broke away from Northern Middle English around about 1450 — also pre-dating the Act of the Union and the independence movement.

If you want to learn more about the history of the Scots language, my friend Jason wrote a great round-up: Scots: a leid to rival any other

Bilingual roads signs were a Labour / Lib Dem policy

Whenever someone moans about the SNPbad spending money on bilingual road signs, you can enjoy a moment of superiority by letting them know that it was a policy passed by the Labour and Liberal Democrats coalition in 2005 that led to Gaelic roadsigns. It’s called the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005, which was put forward by Labour MSP Peter Peacock and was passed unanimously. It didn’t specifically mention roadsigns but required local authorities to create a Gaelic Language Plan, which for many included roadsigns.

Bilingual road signs don’t cost a fortune either. A Freedom of Information Act request showed that only £3,510 had been spent by Transport Scotland on Gaelic road signs and safety material between 2014 and 2017. Bilingual road signs are also common in many countries across the world.

Gaelic Medium Schools were introduced by the Tories

Gaelic Medium Education has existed in Scotland since 1985 when the Conservatives were in power at Westminster and Scotland didn’t yet have its own Parliament. It was the then Scottish Secretary, George Younger (a fluent speaker), who began funding Gaelic initiatives in Scotland, including Gaelic Medium Education.

Scottish Protestants most definitely speak Gaelic

The ugly side of Unionist Twitter, specifically the Loyalist and Orange Order wing, occasionally likes to chime in saying that they’ll never touch Gaelic because it’s not in the Protestant nature. I’ve also had people (very rarely) question my religious background based on my Gaelic name. I don’t practice any religion and consider myself agnostic but my mum is practising Presbyterian and both sides of my family are of Protestant background. There are also Gaelic-speaking congregations in the Church of Scotland across the country, including Glasgow and Edinburgh.

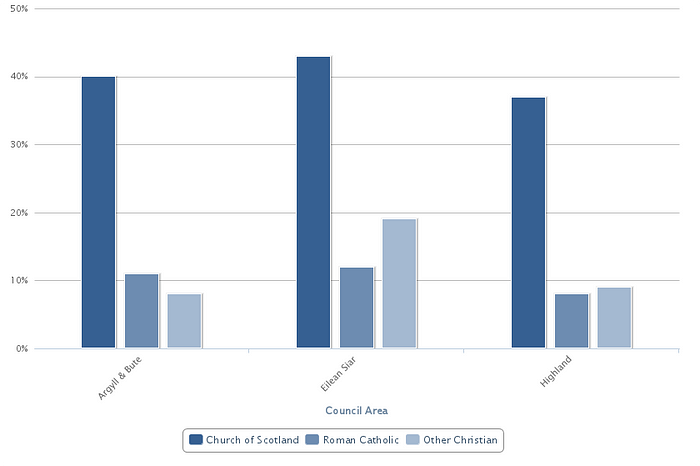

I also decided to dig into the 2001 Census data (which is available to everyone here) to see which denominations were more common in Gaelic speaking council areas. Here are the results:

We also can’t forget about the Lewis & Harris Rangers Supporters Club, which even has some Gaelic in its Twitter bio! Sinne Na Daoine indeed!

Look, these Union Jack accounts are being their usual bigoted selves and I almost considered not covering this…but alas the No Surrender lot like to sprout out anti-Gaelic nonsense on the regular so I’m pointing out their inaccuracies.

It’s not as straightforward in Northern Ireland either

A common reason I’ve received for the confusion is the situation in Northern Ireland, where Republicans traditionally support Irish and Unionists typically support Ulster-Scots. It’s not unusual to see Irish Twitter and Scottish Twitter ending up in the replies of each other when Scots, Ulster-Scots, Irish, or Scottish Gaelic are being mentioned.

My usual comeback to this is that Ireland and Scotland are two different places, albeit with a lot of movement. As mentioned earlier, Gaelic broke off from Middle Irish in roughly the 4th -5th Century, allowing it time to become a language in its own right with its own set of challenges.

The thing is it isn’t that straightforward in Northern Ireland either. I’m no expert on Northern Ireland’s politics or history so I pulled aside Rían Ó Díomasaigh who exposed the Scots Wikipedia, has a degree in History from Queens University Belfast and publishes Ulster-Scots Word of the Day videos on Twitter. Here’s what he had to say:

“In Northern Ireland it’s Unionists who most often champion the Scots language, so the argument that [Scots] is inherently associated with nationalism doesn’t really hold any water. And the fact unionists here aren’t bothered by the fact that the most famous writer of Ulster-Scots literature — James Orr — was an Irish Republican rebel, demonstrates to me that it transcends boundaries and isn’t the exclusive property of any political or ethnic or religious persuasion.

“In a sad way, the opposite holds true as well; the fact that Ulster-Scots was historically associated with Republicanism hasn’t endeared it to the minority of modern Irish Republicans who mock and decry it at all. So when you look at the situation in both Northern Ireland and Scotland, to me it doesn’t seem to be a matter of unionism vs nationalism, it’s just Scots speakers vs bigots who have an inexplicable objection to the language.”

Gaels have asked Independence organisations to not appropriate Gaelic words

It’s not particularly unusual to see Yes groups and supporters appropriating Gaelic words even when they can’t speak the language and haven’t done much to help protect it. Very recently Alex Salmond launched his Alba Party and proceeded to mispronounce the word Alba (it’s Ala-puh, not Al-ba). A massive Twitter debate followed where certain Indy supporters were claiming that Al-ba is the English pronunciation of this Gaelic word (the English word for Alba is Scotland, just like Spain is English for España) and that Gaelic speakers were being sensitive.

A similar debate erupted not that long ago when All Under One Banner tried to set up a new group called Yes Alba, even though Yes Alba already existed and was founded by Gaelic speakers for Gaelic speakers. Many AUOB supporters didn’t back down when this was pointed out to them, and claimed that the word Alba does not belong to Gaelic speakers.

As I’ve already owned, I’m not a Gael. But I’ve witnessed enough Gaelic-speakers asking other Scots not to appropriate Gaelic words that I’m going to call it out as well. If a Yes group tried to appropriate Doric words (and didn’t even pronounce them correctly) I’d be angry too. Using Scots and Gaelic to appear more Scottish or more in favour of independence is cringy at best, damaging for the language at worst.

For more reading, there’s an excellent five-part series on Bella Caledonia on Gaelic Promotion as a Social Justice Issue. Here’s my favourite quote from it (which was just as much a learning curve for me too!):

“…learning Gaelic without appropriating Gaelic identity definitely is in the best interest of Gaels, because the more people there are who speak their language, the more pressure can be exerted on the state to give that language and its community the protections it needs to survive. Thus, claiming to be a Gael on the sole basis of learning Gaelic is bad allyship...”

To finish off…

When I’ve been speaking to people who genuinely believe that both languages are nationalist tongues (or dead), their tempo changes when they are presented with the facts. For example, when I tell people that my mum speaks Doric at home but English out and about, some people will respond with curiosity as they realise their perception of the world was skewed by their own experiences.

Sometimes I think anti-Gaelic and anti-Scots Unionists know what they’re doing when they claim that Gaelic and Scots are nationalistic tongues that we’ll be forced to speak if Scotland becomes independent. It’s a last-ditch attempt to make people want to stay in the Union in the fear that they’ll need to spend time learning a new language. It also creates a divide where Scottish people who can only speak English might get their back up about independence thinking it’s not for them based on linguistics.

This myth can then grow when independence supporters begin insisting that this binary divide really exists (despite all evidence to the contrary). It’s important that this myth doesn’t gain ground and that it stays on the outer fringes of Twitter. To do that independence supporters can’t jump to the conclusion that someone is a Unionist if they say something negative about bilingual road signs (which they shouldn’t, but it doesn’t make them a Unionist). Instead, engage in a conversation about it being a Labour policy and that Gaelic speakers are taxpayers too and deserve to use services in their language (especially a language with a very long history in Scotland).

I’m a former Unionist and I can assure you that throwing around arguments that don’t hold up against scrutiny is not the way to win an independent Scotland. Appropriating Gaelic or Scots words to sound more Scottish wouldn’t have done it either. If I was still a Unionist today, my reaction to some of the Twitter fights regarding a language I grew up with would be a lot less pleasant than this article. I’ve always cared about Doric’s survival, both as a Unionist and as a Yes supporter, because it holds a special place in my heart and to witness the arguments online is perplexing at best and infuriating at worst.

Just before I finish up I want to make it clear that I'm not saying the issue of saving Gaelic and Scots is apolitical. It is not. Politics are very important to the survival of Gaelic and Scots and played a big part in why both languages became endangered in the first place. I want politicians on either side of the constitutional divide to come together to save it. I’d also ask for politicians who have never shown much interest in saving either language to ask themselves why and research how they could do better.

As I said at the start I’m not here to share ideas on how to save these languages; there are dozens of experts who can design a strategy much better than I could. A starting point, however, is to stop equating support for these languages with support for Scottish independence. It is time that could be used more productively — both when it comes to fighting for an independent Scotland and saving two endangered languages that have a long history in Scotland.